Exploring Black History in Franklin, Tennessee

This post is sponsored by Visit Franklin and Black Travel Alliance

TL;DR: Franklin, Tennessee, isn’t just Civil War battlefields and historic homes—it’s a living monument to Black resilience. Discover the powerful stories behind Hard Bargain, the McLemore House Museum, and Toussaint L’Ouverture Cemetery. Learn how projects like The Fuller Story and groups like the African American Heritage Society are preserving the voices of Black pioneers who built Franklin from the ground up. Black history is Franklin’s history—and it’s time we tell it right.

When walking the streets of Franklin, Tennessee, the history almost feels tangible. From the brick sidewalks to the old storefronts and even the grand Civil War mansions, the charming image is one that many have come to expect. Many know them for their picturesque town that looks like the template for every single Hallmark movie, but to those of us who look closer and listen carefully, Franklin tells another story—a story of resilience, determination, and the enduring spirit of its Black community. A story that demands to be honored.

Hard Bargain sign located outside of the McLemore House

After the Civil War, as the smoke of conflict cleared and Reconstruction began, formerly enslaved Black people in Franklin set out to build new lives in the only world they had ever known. Freedom was hard-won and fragile, but it was a beginning. Communities like Hard Bargain—named for the difficult deals and negotiations once made there—rose up as a testament to Black strength and ingenuity. Families laid foundations, not just of homes, but of futures they dreamed could be better. The name says it all—life in Franklin was never easy, but it was theirs. They created a community full of teachers, preachers, craftsmen, and dreamers, laying foundations that generations would stand upon.

The McLemore House Museum

At the heart of this story is this legacy is the McLemore House. Built in 1880 by Harvey McLemore, a formerly enslaved man turned prosperous landowner, the McLemore House today stands proudly as a museum – managed by the African American Heritage Society of Williamson County. To step inside is to step into a living archive of Black life in Franklin during Reconstruction and beyond. Every wooden floorboard and carefully preserved photograph reminds visitors that Black history is not just a story of suffering but also of survival, growth, and excellence.

The McLemore House Museum stands not only as a place of memory but as a declaration: We were here. We thrived. We mattered.

We were here.

We thrived.

We mattered.

We were here. We thrived. We mattered.

Toussaint L’Ouverture Cemetery info sign

Not far away, on the edge of town, lies Toussaint L’Ouverture Cemetery. Founded in 1869 and named after the Haitian revolutionary who refused to be shackled, this sacred ground is the final resting place of the pioneers of Franklin’s Black community—mothers, fathers, veterans, entrepreneurs—people who, despite living under the constant threat of racial violence and systemic injustice, built a world for themselves and their children. Standing among the weathered stones, it’s impossible not to feel the weight and beauty of their sacrifices. Their weathered headstones tilt under the Tennessee sky, but the spirits of those buried there stand tall.

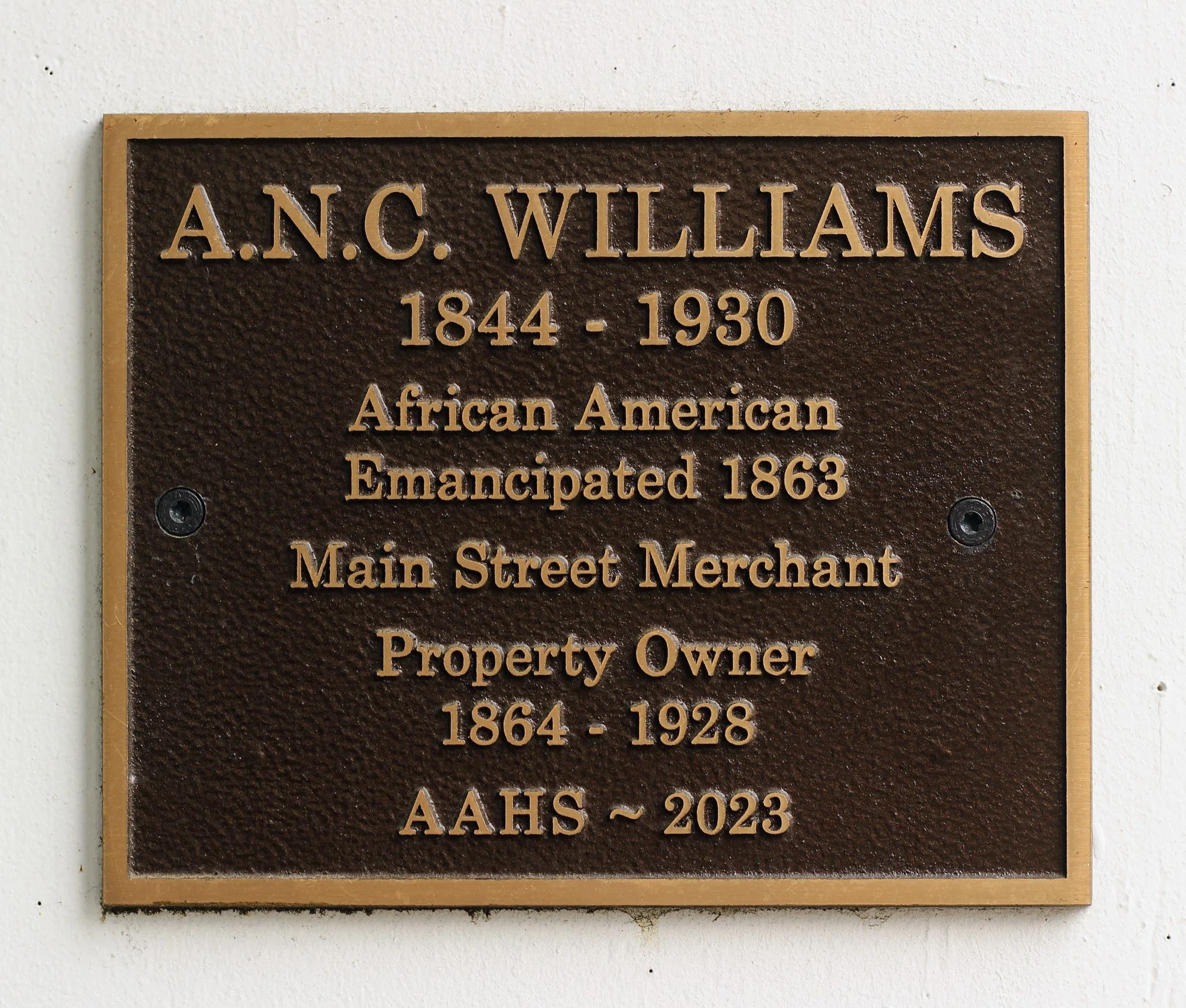

One of the pioneers laid to rest at the Toussaint L’Ouverture Cemetery is A.N.C. Williams. Born into slavery in 1844, he went on to establish Franklin's first Black-owned business—a shoe repair shop on the town square– upon his emancipation on 1863. Though the original shop was destroyed during the Battle of Franklin in 1864, Williams's resilience led him to reopen and eventually expand his enterprise into a general merchandise store on Main Street, serving both Black and white customers during the era of segregation. Proof of his legacy exists today with a historical marker at the site of his former store on Main Street and a street named in honor of his memory.

Each name etched in stone is a story—a testament to Black life, Black faith, Black endurance. Cemeteries like Toussaint L’Ouverture are not places of despair; they are gardens of memory, places where we can honor the seeds our ancestors planted with their lives.

Carnton Plantation's history is deeply entwined with the lives and labor of the enslaved African Americans who sustained it. Established in 1826 by Randal McGavock, the plantation expanded from housing 11 enslaved individuals in 1820 to 44 by 1860, who lived in cabins south of the main house and worked in various capacities, including agriculture, domestic service, and skilled trades. Among them was Mariah Reddick, born around 1832, who served as a housekeeper, nurse, and midwife for the McGavock family across four generations. During the Civil War, she was sent to Montgomery, Alabama, to avoid emancipation by Union forces and worked as a nurse there. After the war, Reddick returned to Carnton as a freedwoman, becoming a respected midwife in Franklin's community. In recent years, efforts have been made to honor the contributions of the enslaved at Carnton. While visiting, we were able to be amongst the first to see the newly commissioned busts of Mariah and Anna.

The commission of these busts is just part of the efforts being made by The Battle of Franklin Trust to recognize everyone who lived at Carnton. Another part of the effort involves life-sized representations of the enslaved people on the property, noting their age and gender. This physical representation creates a visceral reaction, breaking the plane that exists for most people between nameless people who weren’t even seen as human and humanizing them. Perhaps with more intentional efforts like these, more people will be able to undeniably face history and truly bear witness to avoid repeating it.

For too long, Franklin’s official story neglected these truths. History here was often told through the lens of the Confederacy, a narrative that glossed over or outright erased Black experiences. But history is not static, and in Franklin, a new chapter is being written.

In recent years, Franklin has begun recognizing its fuller story more openly. The Fuller Story project, initiated by local leaders, historians, and community members, added new historical markers downtown and erected the striking “March to Freedom” statue in the Public Square. This statue, depicting a Black Union soldier, stands boldly near the Confederate monument. With his back facing the courthouse, the statue symbolizes the history of Black men walking into the courthouse as enslaved men and walking out with papers approving them to fight for their freedom.

It reminds us that the Black experience is not an addendum to American history; it is foundational to it.

Today, organizations like the African American Heritage Society of Williamson County work tirelessly to preserve and share these stories, ensuring that the richness of Franklin’s Black history is not lost to time. Their efforts feel personal, urgent. Because to honor these ancestors is to affirm their lives mattered—not just in the shadows of oppression, but in the brilliance of their achievements, their hopes, their humanity.

For those of us who love Black history, Franklin is more than just a quaint town with a “complicated past”. It is a living, breathing monument to the strength of our ancestors. It is proof that even in places marked by great pain, Black excellence has taken root and flourished. And every time we remember their names, walk the paths they carved, and tell their stories with care and pride, we bring them forward with us into the light.

Franklin’s Black history is not a footnote—it is the very heartbeat of the city’s true story. And for that, we remember, we honor, and we continue to tell it.